Roisin Conneely

Last week, we introduced you to a worm you probably don’t ever want a real-life introduction to, the parasite behind the neglected tropical disease, schistosomiasis. Now, let’s dive in to the life cycle of this critter, how it enters the body and what damage it does there, and how the disease may be detected and treated.

Life cycle

Eggs of the schistosome are released in the faeces or urine of its host. If these eggs happen to come into contact with freshwater, they will hatch and release miracidia (a free-swimming larval stage of the parasite). These miracidia swim using cilia on their surface and infect freshwater snails, which are known as the parasite’s intermediate hosts. Different species of schistosome will infect different species of snail, for example:

- S. mansoni → Biomphalaria snails

- S. japonicum → Bulinus snails

- S. haematobium → Oncomelania snails

Once inside the snail, the miracidia develop into sporocysts (an encysted zygote). The life cycle stages of the parasite whilst inside the snail include two generations of sporocysts. The sporocysts travel to the snail’s heapatopancrease and start to divide, producing thousands of cercariae. These free-swimming cercariae emerge from the snail host daily, according to circadian rhythm, which is dependent on ambient temperature and light.

Upon their release, infective cercariae swim and penetrate the skin of a human host. This is when they shed their forked tail and become schistosomulae. Once in the body they travel via the circulatory system to the liver, where they eventually take up residence in the liver sinusoids. Fun fact, juvenile S. mansoni and S. japonicum worms will develop a delightful oral sucker once they arrive at the liver, to enable them to directly feed on red blood cells, how charming!

Just in case matters weren’t disturbing enough, let’s move on to the next step in the life cycle. A male worm surrounds a female and encloses her in his gynacorphoric canal, where she will remain for the rest of their adult lives (how cosy). As the male feeds on the host’s blood, some of it will get passed on to the female, and she also receives chemicals from him to complete her own development.

Worm-pairs of the S. mansoni and S. japonicum variety will then relocate to the mesenteric or rectal veins, whilst S. haematobium pairs travel to the perivesical venous plexus of the bladder. Once in their new destinations, the female will deposit eggs in small venules of the portal (spleen, pancreas, gallbladder and abdominal section of GI tract) and perivesical (bladder) systems. S. mansoni and S. haematobium can produce between 20-300 eggs per day, whilst S. japonicum may release 500-3500 on a daily basis.

Eggs are progressively transported toward the lumen of the intestine (for S. mansoni and S. japonicum) and of the bladder and urethra (S. haematobium), allowing them to be released from their respective orifices, ready to start the cycle all over again.

DiDiagnosis[/caption]In endemic regions, diagnosis takes multiple factors into account, such as a review of symptoms and residence history, to determine whether contact with a parasite may have occurred. Alongside this, examinations of stool and/or urine are carried to look for the presence of eggs.

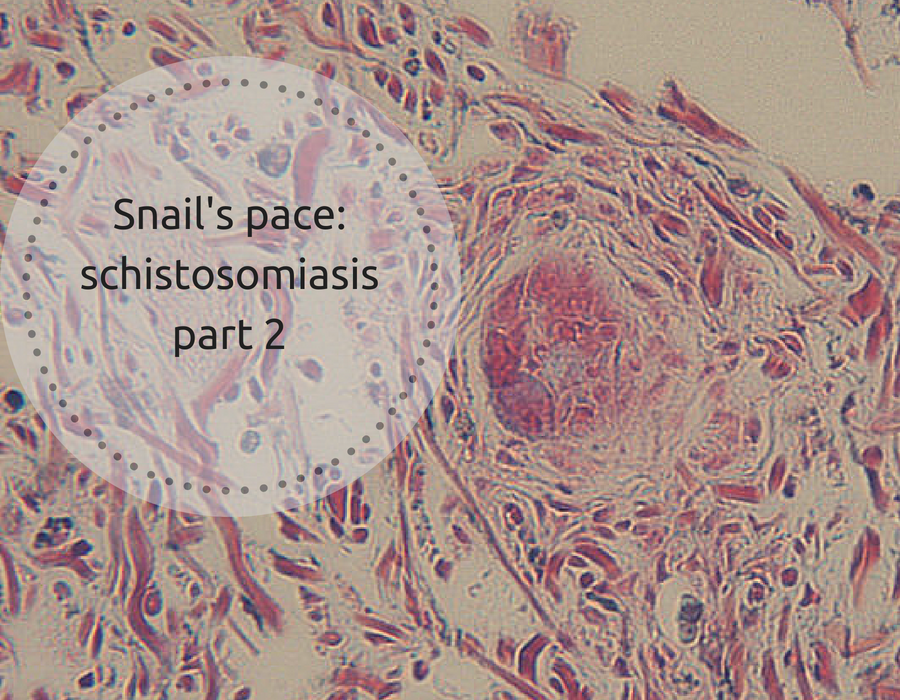

In non-endemic regions, a review of travel and residency history is crucial. In addition to standard stool and urine tests, endoscopic examinations of the bowel and bladder may also be carried out. Furthermore, biopsies may egg-containing granulomas.

Treatment

The drug of choice for schistosomiasis, praziquantel is used to kill cercariae and adult worms, but is less effective agains juvenile parasites. It’s taken orally and has a cure rate of 60-90%. The World Health Organisation (WHO) recommends that, in villages where over 50% of children present blood in the urine, then everyone in the community must receive drug treatment. The drug is not licenced for human use in the UK, but may be prescribed on a named patient basis.

Control measures

As mentioned above, mass drug treatment of whole villages is a major part of controlling this disease in areas of infection. Another option is reducing the number of snails in the locality, removing the intermediate hosts of the parasite. Molluscicides such as acrolein, copper sulfate and niclosande can be used to reduce snail populations, along with the introduction of their natural predators, such as crayfish.

However, the chemicals from such snail killing compounds may have a negative effect on other harmless species nearby. Additionally, if treatment isn’t maintained then snails will eventually return to the ponds. Plus, over time, snails may grow resistant to certain molluscicides.

Preventative steps

If you’ve been well and truly put off ever being close to a freshwater pond again, we don’t blame you. However, if you do plan on visiting any disease risk areas, there are some measures you can take to reduce your risk of becoming a piece of schistosome real estate.

- Avoid swimming/paddling in freshwater

- Drink safe and clean water (schistosomiasis can’t be transmitted by swallowing contaminated water, but contact with the lips could cause an infection)

- Water used for washing should be sterilised first

- Make sure to dry with a towel properly after any freshwater exposure.

Freshwater, marine and coastal pollution | Marcus Ampe's Space

[…] Snail’s pace: schistosomiasis part 2 […]