Madeeha Hoque

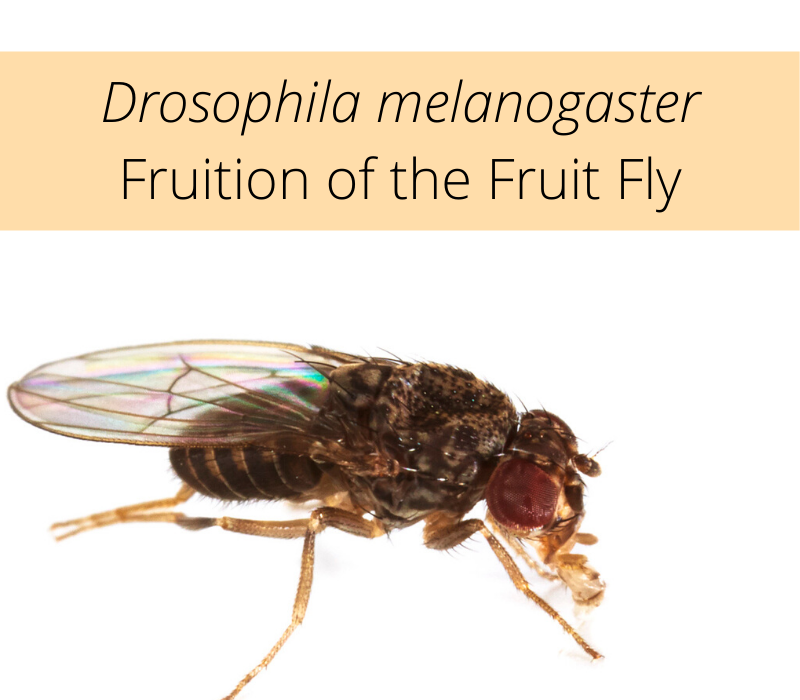

Drosophila melanogaster – more commonly known as the “common fruit/vinegar fly”, is a popular organism relating to heavy importance within the scientific field of research. The term drosophila translates to “lover of dew”, which relates to the fact that this species of fly flourishes well in areas where the availability of water is abundant.

First described by Johann Wilhelm Meigen in 1830, there have been many variations and suggestions of the classification for its genus and species since. Musca cellaris was suggested by Linnaeus in 1758 and Drosophila aceti was suggested by Heeger in 1851, along with many others. However, it is now widely accepted that the genus and species of this organism falls under Drosophila melanogaster. Part of the family Drosophilidae, D. melanogaster has a total of nine sibling species subgroups, including the D. yakuba, D. orena and D. erecta.

What separates Drosophila melanogaster from other species of fruit flies are their ‘pectinate’ aristae, which are hair-like structures on their short antennae. They have a three-body segmented structure, with three pairs of legs and bright, large, red eyes (creepy). They also have a proboscis-like mouth part for sucking up liquids from food. (Don’t try that at the dinner table)

D. melanogaster undergo metamorphosis when maturing into adults. Their life cycle begins with a larval stage, which moves onto to pupal stage and results with the adult stage. (I’m sure we can all relate as the best stage, right? Right??) The larval stage mainly consists of moulting from the egg, whereas the pupal stage sees that the organism begins to develop visible body parts. Sexual dimorphism is present in D. melanogaster and this is seen upon full development. Adult males are usually between 2-3mm in length, whereas females are typically much larger. Sex is also distinguishable by the abdomen – with females having generally pointed and elongated tips, in comparison to the rounded abdomen of the males. Black pigmentation found on the tip of the abdomen can also be used to distinguish between sexes, with greater amounts of pigmentation only found on males.

Drosophila melanogaster lay their eggs on ripen, unripen or rotting fruit – so basically any fruit. No one is safe.

They become fully fledged adults and reach sexual maturity within at least a week after hatching, depending on the temperature of their surrounding environment. They favour temperate and warm climates as opposed to chilled environments since they thrive better in humidity – hence they are not found in areas where extreme climates are prominent, such as deserts or tundra. This is ultimately due to the presence of vegetation being a vital factor for the development of these flies. Their reproductive behaviour is sexual and fertilisation occurs internally. Males of the species have an adaptation of their genitalia known as a ‘sex comb’ (kinky) which aids their ability to successfully reproduce. Research has shown that a lack of this adaptation can actually hinder reproductive success of males.

These fun fruit flies can usually be found in many places associated with a plethora of human activity, such as gardens, homes and restaurants, where there is an abundance of food available – they are even often found near bins where there may be wasteful decaying food present. Talk about recycling! As mentioned earlier, Drosophila melanogaster feed by using their proboscis to extract sugars, such as fructose, from the inside of various fruit. A study done by Jeeva Jacob has proven that D. melanogaster prefer to feed on foods which are rich in sucrose or yeast extracts. They can determine which foods contain high levels of sugar by their hair-like structures called sensilla, which are located on various parts of their bodies, such as on their proboscis and legs.

These sensilla contain around 68-70 gustatory receptors which enable them to determine efficiently between foods with either high sugar or salt content – allowing them to quickly find their preferred items to feed from.

This species has an important role within certain ecosystems as they are the main vector for organisms, such as bacteria, fungi or even yeast. Although D. melanogaster are globally seen as every-day pests to most householders, in the scientific field of research, these flies are far from being undesirable. As well as being known as annoying flies we swat around when trying to eat our food, D. melanogaster have a significant importance in research, due to their short generation cycles and their habit of laying plentiful eggs during each generation. Since they thrive in temperate climates, the species is more or less available to numerous scientists worldwide due to their abundance and ease of accessibility, as well as the low maintenance needed when breeding multiple generations. Due to their incredibly short life cycles and ability to reach sexual maturity in just a week under the correct conditions, scientists everywhere during the past hundred years have been using Drosophila melanogaster as a model organism for studying and playing around with hereditary genetics and mutant genes, shaping our knowledge of the world of genetics to date.

Although Drosophila melanogaster may seem like the average, day-to-day pest in most eyes, we can conclude that beauty is definitely in the eye of the beholder. Proven by many scientists across the globe, this mere insect has provided the world with a wonderful and magnificent specimen to toy with when aiding us in understanding the importance of genes, and will remain to be an abundant source of research for many years of study to come.

Sources:

- Patterson, J., R. Wagner, L. Wharton, 1943, Austin TX: The University of Texas Press “The Drosophilidae of the Southwest”

- L Partridge, B Barrie, K Fowler, V French, 1994, Evolution, “Evolution and development of body size and cell size in Drosophila melanogaster in response to temperature”

- A. N, 2008, Behaviour Genetics “Sex combs are important for male mating success in Drosophila melanogaster”

- Laurence D. Mueller, 1981, “The Evolutionary Ecology of Drosophila”

- Jeeva Jacob, 2013, “A Study on Food Preference in Drosophila”

- N. H. S., 2013, Journal of the Royal College of Physicians in Edinburgh “Drosophila melanogaster: a fly through its history and current use”

- http://eol.org/pages/733739/details

- https://www.aub.edu.lb/fm/medicalresearch/AnimalCareFac/Documents/Document%209-%20Drosophila%20Melanogaster.pdf